Stretching across mountains, deserts, and plains, the Great Wall of China is one of humanity’s most awe-inspiring achievements. More than just a wall, it’s a symbol of perseverance, ingenuity, and China’s rich history. Let’s unravel its secrets!

1. How Long Is the Great Wall of China?

The Great Wall is 21,196 km (13,171 miles) long, including all its branches and sections built over centuries. To put this into perspective:

It’s roughly half the length of the Earth’s equator.

Only about 8% of the wall remains well-preserved; the rest has eroded or been reclaimed by nature.

2. When Was the Great Wall Built?

The Great Wall wasn’t built in one go—it evolved over 2,300 years:

7th Century BCE: Early walls were constructed by warring states like Qi and Chu.

221–206 BCE: Emperor Qin Shi Huang connected and expanded existing walls to defend against northern nomads.

14th–17th Centuries CE: The Ming Dynasty built the iconic stone-and-brick sections we see today.

The Great Wall was built and renovated over 2,300 years across multiple dynasties. Below is a summary of key periods and contributions:

Dynasty |

Time Period |

Key Developments |

Zhou Dynasty |

7th–8th century BCE |

Early walls and beacon towers constructed by feudal states like Qi and Yan715. |

Warring States |

5th–3rd century BCE |

Independent walls built by rival states (Qin, Zhao, Yan) for defense79. |

Qin Dynasty |

221–206 BCE |

Emperor Qin Shi Huang unified and expanded existing walls, creating the first "10,000-li (5,000 km) wall"915. |

Han Dynasty |

206 BCE–220 CE |

Extended westward to protect Silk Road trade; longest stretch in history (nearly 10,000 km)913. |

Ming Dynasty |

1368–1644 CE |

Most iconic stone-and-brick sections built, including Badaling and Mutianyu. Total length: 8,851.8 km1215. |

Qing Dynasty |

1644–1912 CE |

Construction halted; focus shifted to diplomatic relations with northern tribes7. |

Total Length: 21,196.18 km (all dynasties combined).

3. Why Was the Great Wall Built?

The Great Wall emerged as a multifaceted engineering marvel addressing three core national priorities across dynasties:

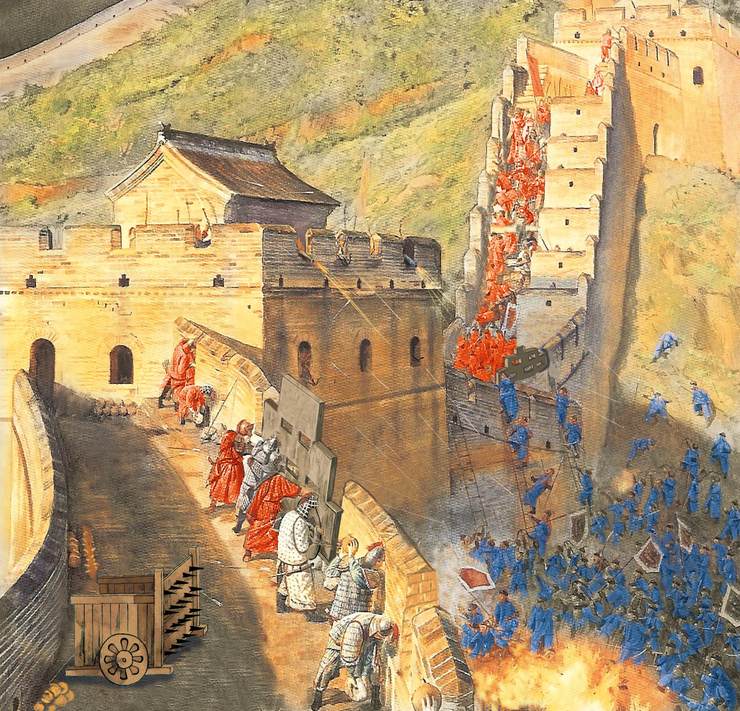

Strategic Military Defense

Primarily conceived as a fortified barrier, it countered persistent threats from northern nomadic tribes like the Mongols and Xiongnu. Its elevated watchtowers enabled early detection of invaders, while steep gradients and 15-30 foot heights physically hindered cavalry charges. The wall's psychological impact proved equally vital – its imposing presence symbolized imperial might, deterring potential aggressors through perceived invincibility.

Integrated Communication Network

Beacon towers spaced along the wall formed an ancient "optical telegraph" system. Guards transmitted urgent military alerts across vast distances using smoke signals by day and fire by night, enabling rapid troop mobilization. Historical records indicate messages could traverse 500+ km within 24 hours – unprecedented speed for pre-modern eras.

Economic Regulation Hub

Beyond warfare, the wall governed Silk Road commerce through guarded passes like Jiayuguan. Officials monitored trade caravans, collecting tariffs on goods (silk, tea, spices) while preventing smuggling. This system also regulated population flows – travelers required documentation to pass, curbing unauthorized migration between agricultural and nomadic zones.

Cultural & Political Symbolism

Though not its original purpose, the wall gradually embodied Chinese civilization's resilience. Its continuous expansion under successive dynasties (Qin, Han, Ming) reflected evolving concepts of territorial integrity and centralized authority. The Ming reconstruction particularly emphasized this symbolism, using uniform bricks stamped with construction dates to showcase bureaucratic precision.

The wall's enduring legacy stems from this adaptive functionality – initially a military asset, it organically became an instrument of economic control, cultural identity, and technological showcase. Modern studies estimate over 1/3 of its total length served non-combat roles like trade route supervision.

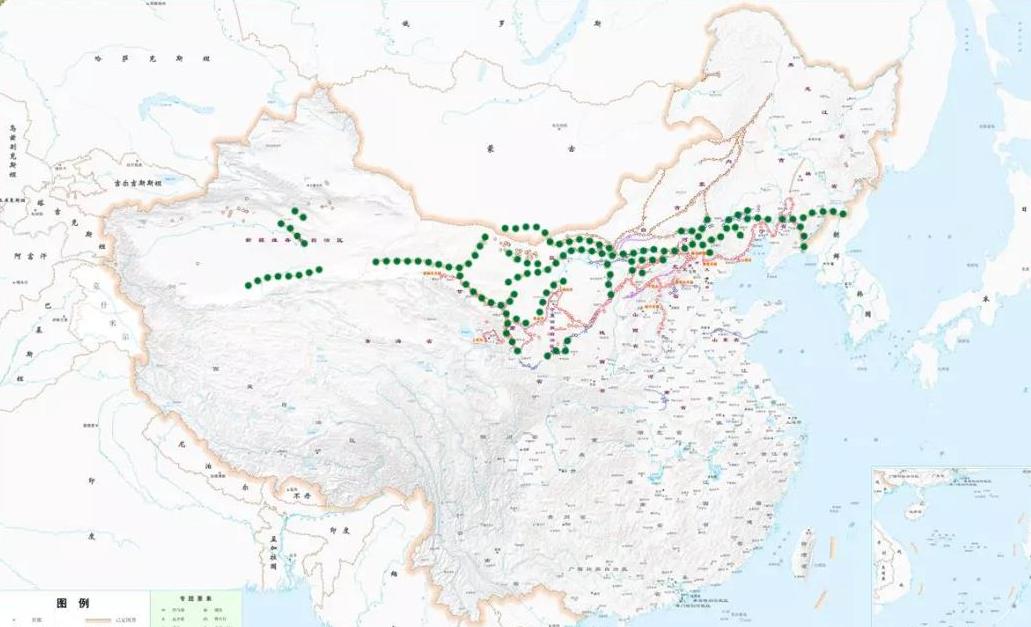

4. Where Is the Great Wall Located?

Stretching across northern China, the Great Wall spans approximately 15 provincial-level regions, including Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, Shanxi, Inner Mongolia, and Gansu.

Its eastern terminus traditionally marks Shanhaiguan Pass in Hebei Province, where the wall meets the Bohai Sea—a section poetically named Laolongtou (Old Dragon’s Head) for its resemblance to a dragon dipping into the waves.

Modern archaeological surveys, however, extend its recognized eastern origin to Hushan Mountain in Liaoning Province.

The western endpoint remains Jiayuguan Pass in Gansu Province, a strategic gateway along the ancient Silk Road.

While the Wall’s full historical length exceeds 21,000 km when accounting for overlapping dynastic constructions, the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) sections—measuring 8,851.8 km—form its most iconic and preserved portions.

These traverse diverse terrains, from the Yan Mountains near Beijing to the deserts of Ningxia, adapting to ridges and valleys for defensive advantages.

Beijing’s surrounding areas host the most frequented sections due to accessibility and restoration efforts. Key highlights include:

Badaling: Located in Yanqing District, this meticulously restored Ming-era segment features watchtowers and steep gradients, earning UNESCO World Heritage status in 1987.

Mutianyu: Blending natural scenery with architectural diversity, this section in northern Beijing boasts unique "arrow windows" and parapet designs.

Jinshanling: Straddling Beijing’s Miyun District and Hebei’s Luanping County, it’s renowned for its 67 well-preserved watchtowers within a 10.5 km stretch.

Other notable segments include Huangyaguan in Tianjin with its zigzagging paths, and Jiayuguan’s fortress in Gansu, showcasing Ming military engineering. Despite its fragmented state today, the Wall’s geographic reach—from coastal plains to arid northwestern frontiers—reflects its historical role as both a defensive network and a cultural corridor.

5. Who Built the Great Wall?

Millions contributed over centuries:

Laborers: Peasants, soldiers, and prisoners. Many died during construction, earning the wall the grim nickname “The Longest Cemetery on Earth.”

Emperors: Qin Shi Huang (Qin Dynasty), Emperor Wu (Han Dynasty), and Ming rulers like Yongle spearheaded major expansions.

6. Legends of the Great Wall

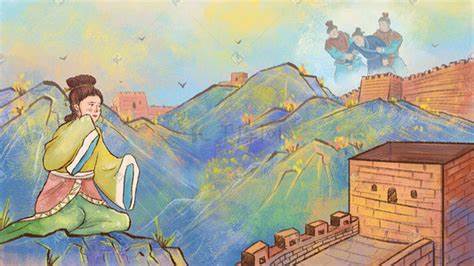

Meng Jiangnü's Lament

This enduring folk narrative, recognized as China’s earliest "protest literature,"originated from historical accounts in Zuo Zhuan (5th century BCE) about a grieving widow named Qi Liang’s wife. Over centuries, storytellers merged this tale with Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) Great Wall construction lore.

The story centers on Meng Jiangnü, born miraculously from a shared gourd vine between two childless families. Her brief marriage to scholar Fan Xiliang—interrupted when he’s forcibly conscripted for wall-building—drives her epic journey northward. Braving harsh winters with handmade burial clothes, she discovers her husband’s bones entombed within the wall. Her three-day lamentation (or seven days in some versions) symbolically collapses 800 li (≈400 km) of masonry, exposing imperial cruelty through supernatural imagery.

Beyond romance, the legend embodies resistance:

Social critique: Condemns Qin Shi Huang’s tyranny and forced labor systems.

Feminine resilience: Challenges patriarchal norms through her defiance of both conscription officers and Emperor Qin’s marriage proposal.

Cultural memory: Over 40 sites claim association, including Shanhaiguan’s Jiangnü Temple where she supposedly leapt into the sea.

Designated intangible heritage in 2006, its variations across provinces and adaptations in operas demonstrate its role as a collective trauma narrative for laborers’ families.

7. Structure of the Great Wall

a. Core Defensive Walls

The backbone of the Great Wall consists of layered walls averaging 7–8 meters in height, constructed using materials adapted to local geography. In mountainous regions, quarried stones formed sturdy barriers, while desert sections utilized sand and tamarisk branches. The walls’ cross-section tapers from a 6–7m-wide base to a 4–5m-wide top, wide enough for five horses to trot abreast. Strategic modifications included:

Parapets: Outer "crenellated walls" with observation holes and arrow slits

Inner barriers: Lower "lady walls" on the sheltered side to protect defenders.

b. Surveillance & Communication Network

Watchtowers: Spaced at arrow-shot intervals (~200m), these multi-story structures served as garrisons, armories, and observation posts. Their elevated platforms allowed guards to monitor vast territories.

Beacon towers: Positioned beyond the main walls, these relay stations transmitted alerts via smoke by day and fire by night, capable of signaling across 500+ km within 24 hours.

c. Strategic Passes & Fortifications

Key access points like Jiayuguan and Shanhaiguan featured layered defenses:

Wengcheng: Semi-circular "barbican" traps outside main gates to ambush intruders

Luocheng/Yicheng: Secondary walls extending from fortresses to control flanking routes

Massive gates: Reinforced with iron nails and crossbeams, some weighing tons

d. Military Infrastructure

Garrison forts: Self-contained complexes like Juyongguan housed troops, with barracks, stables, and administrative offices

Ramparts: Broad walkways (5–6m wide) along wall tops, paved with anti-slip diagonal bricks

Hidden passages: Internal arched gates and stone staircases allowed rapid troop movements

e. Adaptive Engineering

Builders demonstrated remarkable flexibility:

Mountain sections followed ridges, exploiting natural cliffs as "pre-built walls"

Desert segments used reed-reinforced earth to withstand shifting sands

Marshland areas employed wooden pilings as foundations

8. Visiting the Great Wall: Tips for Travelers

Best Time to Visit: Spring (April–May) or autumn (September–October) for mild weather.

Avoid Crowds: Explore lesser-known sections like Huanghuacheng or Gubeikou.

Stay Safe: Wear sturdy shoes for steep, uneven steps.

Why It Matters Today

The Great Wall isn’t just a relic—it’s a testament to human ambition and resilience. Walking its ancient stones, you’re tracing the footsteps of soldiers, traders, and emperors who shaped China’s destiny.