Welcome to the mesmerizing world of Peking Opera (京剧 Jīngjù), a 200-year-old art form that combines music, acrobatics, martial arts, and storytelling into a vibrant cultural experience. Recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, Peking Opera offers a window into China’s history, values, and artistic genius. Let’s unveil its magic!

1. Introduction & History: The Birth of a Masterpiece

Recognized by UNESCO in 2010 as a masterpiece of intangible cultural heritage, Peking Opera (also called Jingxi or Jingju) represents a relatively young art form compared to older Chinese operatic traditions like Kunqu, which thrived among scholarly elites centuries earlier. Emerging in the late 18th century, Peking Opera evolved through the blending of regional styles, particularly Anhui and Hubei operas. Its foundation drew from Han Opera’s musical innovations, notably the Xipi and Erhuang melodies that remain central to its performances.

The art form’s origins can be pinpointed to 1790, when Anhui troupes performed in Beijing for Emperor Qianlong’s grand birthday celebrations. Over subsequent decades, collaborations between Anhui and Hubei performers refined its distinct identity, solidifying by the mid-19th century. Initially male-dominated, with boys portraying female roles, women gradually entered the stage starting in the 1870s. Traveling troupes later popularized the art nationwide, cementing its status as China’s premier operatic style by the 1900s.

Early performances unfolded in teahouse courtyards, where audiences enjoyed lengthy, free shows while sipping tea. By the late 19th century, dedicated theaters emerged, though gender-segregated seating persisted until 1931. Imperial patronage, notably from Empress Dowager Cixi, who commissioned stages in the Summer Palace, elevated its prestige. However, the Boxer Rebellion (1900) devastated Beijing’s theaters, prompting surviving artists to innovate by integrating Western influences and addressing social issues.

The 20th century brought both global recognition and domestic turbulence. Legendary performer Mei Lanfang pioneered international tours in the 1930s while challenging gender norms by training female students. Post-1949, the government promoted revolutionary themes, but the Cultural Revolution (1960s-70s) suppressed traditional works, replacing them with politicized “model operas.” Revival efforts in the 1980s modernized staging, incorporated contemporary themes, and shifted creative control to directors and playwrights.

Modern challenges include adapting archaic dialects through electronic subtitles and pacing performances for younger audiences. Reforms now blend Western aesthetics with traditional face-painting and experimental public performances. State-supported platforms like CCTV’s dedicated opera channel aim to preserve its legacy while embracing innovation, reflecting its enduring yet evolving role in Chinese culture.

Key milestones:

1790: Four Anhui opera troupes performed in Beijing for the emperor’s birthday, laying the foundation.

19th Century: Incorporated Kunqu (refined classical opera) and Qinqiang (Shanxi folk styles).

20th Century: Modernized with female performers (originally all-male casts) and global tours.

2. Performers and Roles: The Four Pillars of Peking Opera

Peking Opera brings stories to life through highly stylized characters, each instantly recognizable by their distinct visual and performance traits. While early classifications included seven role types, modern productions focus on four primary categories, each revealing a character’s gender, age, morality, and even appearance through deliberate artistic choices.

The Sheng represents male characters, ranging from dignified elders to youthful warriors, with subtypes like the scholarly Xiaosheng (young man) or the bearded Laosheng (older statesman). Dan roles portray female figures, from gentle Qingyi (virtuous women) to lively Huadan (maidens or coquettes), with movements and costumes emphasizing grace or vivacity.

More dramatic are the Jing roles—male characters with vividly painted faces whose bold colors and patterns signal their personalities: red for loyalty, white for treachery, or gold for divinity. Their booming voices and exaggerated gestures amplify their larger-than-life presence. Finally, the Chou (clown) injects humor through witty dialogue and acrobatic physical comedy, often marked by a small white patch on the nose.

These roles follow strict conventions in movement, vocal style, and costuming, allowing audiences to "read" a character’s essence at a glance—even without understanding every word. Whether through a general’s majestic strides or a villain’s sinister mask, Peking Opera’s visual storytelling transcends language, making its drama universally engaging

Sheng (生): Male roles, including:

Laosheng (elderly dignified men, e.g., generals).

Xiaosheng (young scholars, often with a falsetto voice).

Dan (旦): Female roles, such as:

Qingyi (virtuous women in elegant gowns).

Huadan (vivacious young girls, like mischievous servants).

Jing (净): Painted-face roles, portraying gods, warriors, or villains. Their bold makeup symbolizes personality (e.g., red = loyalty, white = treachery).

Jing (净): Painted-face roles, portraying gods, warriors, or villains. Their bold makeup symbolizes personality (e.g., red = loyalty, white = treachery).

Chou (丑): Clowns or comic characters, identified by a small white patch on the nose.

Chou (丑): Clowns or comic characters, identified by a small white patch on the nose.

3. Makeup, Staging, Costumes & Music: A Feast for the Senses

Makeup

Peking Opera’s makeup transcends mere decoration, serving as a visual language. While Sheng (male) and Dan (female) roles feature understated, elegant designs emphasizing natural beauty, Jing (painted-face) and Chou (clown) characters transform into living symbols through bold, mask-like Lianpu. Each hue and brushstroke carries meaning: crimson conveys valor, inky black signifies integrity, while ghostly white exposes deceit. Intricate patterns—swirling brows resembling bat wings or jagged lines evoking blades—further telegraph personality traits. Even the clown’s signature white nose patch becomes a universal signal of mischief.

Costume Codes

Robes and attire act as social hieroglyphics. Elaborate Mang dragon robes, reserved for emperors and generals, radiate authority with embroidered celestial motifs. Warriors don Kao armor adorned with tassels and flags, their silhouettes evoking mythical strength. Everyday Zhezi garments distinguish commoners through subtle dyes and fabrics. Footwear, headdresses, and accessories—like a general’s pheasant-feather crowns or a noblewoman’s beaded hairpins—complete these wearable biographies.

Stagecraft & Symbolism

Peking Opera stages are landscapes of the mind. A single table morphs from imperial throne to battlefield lookout through actors’ movements. A swirling whip conjures a galloping horse; trembling hands clutching an invisible cup suggest a poisoned drink. While modern productions may use painted backdrops, the essence remains—audiences collaborate imaginatively, decoding fluttering banners as raging storms or a twirling parasol as a blossoming garden.

Musical Tapestry

The orchestra breathes life into the drama through two contrasting ensembles. Melodic Wenchang instruments like the piercing jinghu fiddle and pearly pipa lute underscore soaring arias and poetic dialogues. The percussive Wuchang section—with its thunderous drums and clashing cymbals—fuels combat sequences and emotional crescendos. Vocal styles shift dramatically between roles: a Laodan (elderly woman) might deliver lines in earthy tones, while a young Qingyi heroine’s ethereal falsetto floats above the orchestra. Traditional Xipi and Erhuang musical modes frame emotions, from fiery confrontations to soulful soliloquies.

Together, these elements form an artistic ecosystem where every gesture, note, and color harmonizes to tell stories that resonate across languages and eras. The operatic "grammar" invites viewers to read between the lines—a crimson-faced general’s stride speaks of honor, while a clown’s pratfall hides wisdom in laughter.

4. Famous Opera Artists: Legends of the Stage

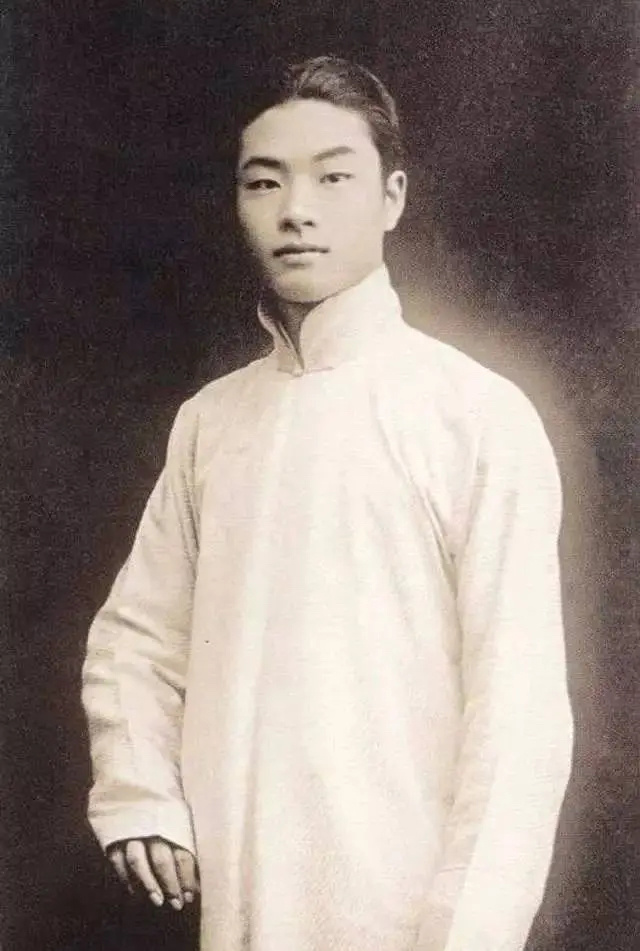

Mei Lanfang (1894-1961)

The global ambassador of Peking Opera, Mei Lanfang revolutionized female role (Dan) performance with his graceful "Mei School" style. Beginning training at age eight, he captivated audiences by his teens with his delicate movements and crystal-clear vocals. Beyond perfecting traditional techniques, he reintroduced lost classics to the repertoire while incorporating martial arts into dance sequences. His groundbreaking international tours—including performances for Charlie Chaplin in Hollywood and Stanislavski in Moscow—made him China’s first cross-cultural opera icon.

Cheng Yanqiu (1904-1958)

Originally trained in martial male roles, Cheng Yanqiu transitioned to female characters under Mei Lanfang’s mentorship, eventually developing his own emotionally charged "Cheng School." His signature vocal technique—resonant yet tender, like "steel wrapped in silk"—could convey a noblewoman’s sorrow with heartbreaking subtlety. Known for his intellectual approach, he often modified scripts to deepen character psychology, creating nuanced portraits of resilient women facing societal constraints.

Shang Xiaoyun (1899-1976)

A dynamic performer who turned personal hardship into artistic triumph, Shang Xiaoyun rose from poverty to become the "Warrior of the Stage." His powerful physique and athleticism (honed through early martial role training) brought unprecedented vigor to female characters. While his soaring vocals earned acclaim, audiences particularly marveled at his acrobatic sleeve-fluttering techniques and dramatic combat sequences. As founder of the Rong Chun School, he nurtured new generations while innovating over 30 original productions.

Xun Huisheng (1899-1968)

The poet of everyday femininity, Xun Huisheng transformed humble maiden roles into art. Sold to a theater troupe as a child, he developed his signature "Xun Style" by blending Hebei folk opera’s earthy charm with Peking Opera’s sophistication. His performances of witty, lovestruck young women—conveyed through coy smiles, playful gestures, and a voice that "lingered like honey"—redefined comic and romantic roles. Rigorous training (including practicing on ice to improve footwork) enabled his seemingly effortless portrayals of girlish innocence.

5. Most Popular Opera Stories: Drama, Love, and Heroism

a. Farewell to the Concubine (霸王别姬)

This tragic masterpiece captures the final hours of Xiang Yu, the undefeated warrior-king of Chu, as his empire crumbles. Surrounded by enemies and facing certain defeat, he shares a poignant moment with his devoted concubine Consort Yu. Rather than burden her beloved, Yu performs an elegant sword dance before taking her own life with his blade—a heart-wrenching display of loyalty that has moved audiences for generations. The opera’s emotional power lies in its contrast between Xiang Yu’s battlefield ferocity and this intimate tragedy.

b. Drunken Beauty(贵妃醉酒)

Showcasing Mei Lanfang’s legendary artistry, this one-act gem reveals the vulnerability beneath imperial splendor. When Emperor Ming unexpectedly stands up his favorite consort Yang Yuhuan for another woman, the abandoned beauty descends into drunken melancholy. Through graceful yet increasingly unsteady movements—miming intoxication with a wine cup, stumbling while fanning herself—the performer transforms what could be comic into profound pathos. The eunuchs’ exaggerated attempts to steady her create dramatic tension between dignity and despair.

c. The Heavenly Maid Scatters Blossoms(天女散花)

A visual spectacle blending dance and spirituality, this opera features a heavenly maiden descending on a rainbow-hued silk ribbon (representing clouds) to test Buddhist disciples with flower petals. Those showered with blossoms must confront their imperfect enlightenment. The lead role demands extraordinary physical control—the performer manipulates long silk scarves with precise movements to create the illusion of floating petals, while singing in an ethereal falsetto. This dreamlike parable about humility in learning remains a technical benchmark for Dan actors.

d. Lady Wang Zhaojun Goes Beyond the Frontier(昭君出塞)

Shang Xiaoyun’s signature work transforms a historical peace offering into an opera of exquisite sorrow. When painter’s deception leads beautiful Wang Zhaojun to be married off to Xiongnu tribes, her journey north becomes a meditation on sacrifice. The most celebrated scene features her riding a "horse" (mimed through rhythmic sleeve movements and quivering pheasant feathers) across imaginary landscapes, her pipa melodies echoing with homesickness. This poetic interpretation of diplomatic marriage highlights the human cost of political decisions.

e. Lady Muguiying Takes Command(穆桂英挂帅)

Mei Lanfang’s final role immortalized this unlikely heroine—a 50-year-old grandmother who dons armor once more to defend her country. What makes Mu Guiying extraordinary isn’t just her battlefield prowess (showcased through martial arts sequences), but her moral courage: she overcomes past betrayals to lead her family into war. The scene where she ceremonially "ties the armor" transforms domestic gestures (adjusting sashes, smoothing wrinkles) into preparations for glory. This celebration of female leadership remains culturally resonant, challenging traditional gender roles.

Each classic represents Peking Opera’s unique storytelling alchemy—where history becomes poetry, emotions transform into movement, and simple props conjure entire worlds. Whether through Consort Yu’s fatal dance or Mu Guiying’s battle preparations, these works prove that what endures isn’t just the tales themselves, but how they’re brought to life through the performer’s art.

6. Where to See Peking Opera?

Beijing:

Li Yuan Theater: Offers short performances with English subtitles.

National Centre for the Performing Arts: Grand, modern productions.

Shanghai:

Yifu Theatre for classic shows.

Hong Kong:

Xiqu Centre for contemporary twists.

Tips for Foreigners:

Opt for shows with subtitles or pre-read plot summaries.

Attend a backstage tour to see makeup and costumes up close.

Try a Peking Opera workshop to learn basic moves or face-painting!

7. Beyond the Stage: Cultural Immersion

Teahouse Performances: Sip tea while watching excerpts in Beijing’s Laoshe Teahouse.

Museums: Visit the Peking Opera Museum in Beijing for historical artifacts.

Souvenirs: Buy hand-painted masks or miniature figurines as keepsakes.